My two German cousins greet me at the undertaker. I’ve just come direct from Frankfurt airport to help prepare for my grandmother’s funeral.

“I picked out these clothes, don’t you think Oma will look so well?” The first sister wants me to know she is taking the lead…but, I swear she has found the shabbiest items in my grandmother’s smart and tailored wardrobe.

Now the other sister adds, “And I found this ring…I thought it was her wedding ring, but now I’m not sure. There’s a date engraved, January 1939…but wasn’t your mother born in May?”

My eyes meet her look, her delivery coy. Is she baiting me or does she really not know? “Yes, my mother was born May 1939.” I say no more, no less; I am not giving her the satisfaction of acknowledging her inference.

She makes one more pass. “Maybe this ring meant something else.”

“Yes. Maybe.”

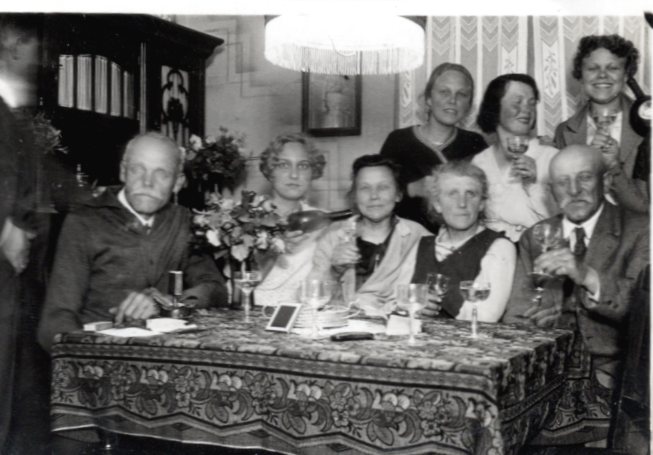

Hmmm…what else doesn’t she know? Just because I live an ocean away, am I the only one who knows these stories? Like how my grandmother, the youngest of 11, almost came to the U.S. at 5 with her oldest sister Agnes, who intended to raise her as her own—recently married Agnes, who was hoping to relieve their bereft mother struggling with the grief of recently losing two children to typhoid while enduring the economic hardships of post-WWI Germany.

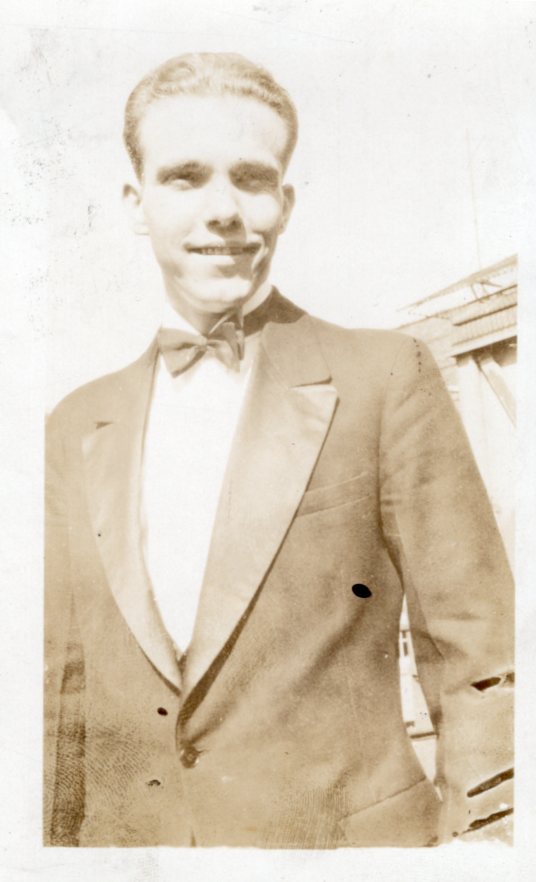

Surely my cousin can’t be the only one who noticed my grandmother’s obsession with reading and re-reading The Thorn Birds. But does she know about the seminarian that grandma/Oma tried to follow when he left for Berlin…the one who subsequently disappeared under the Nazi regime? The same teenager who defiantly climbed out her bedroom window to meet a beau on the night her father banned her from wearing earrings…the young woman with the piercing blue eyes who eventually met the police chief’s son, the dashing medical student on the fencing team…the eventual bon vivant and serial womanizer…my grandfather.

When most of my mother’s family immigrated to the U.S., they took many family stories with them…and spun new ones. And then they had few or no kids. And then they and the kids died. And then the next generation of those left behind in Germany didn’t care. When my parents died, this only child became acutely aware she was the last one left in the family. Left with a treasure-trove of photos, letters and diaries…and no one to talk to. The hardest thing when you are the gatekeeper of the family stories…and secrets…are the questions. The questions you should have asked when you had the chance…and the ones you didn’t know to ask until it was too late. Questions small and big.

Do I love Chinese food because my father ate well while running deliveries for a Chinese laundromat or because Chinese food was all my mother could stomach during her bedridden pregnancy with me? Was I pre-destined to love to cook because I was named after the aunt who founded a bakery or because there were so many relatives in the food industry? Do I jump at sudden noises, loud or small, because my five year old mother lived through an incendiary bombing obliterating her hometown?

When I reflect on what I remember, what was truth and what was bravado? When big personalities live even bigger lives, they are entitled to a bit of embellishment. They didn’t know the Internet and Ancestry.com would fill in the blanks decades later.

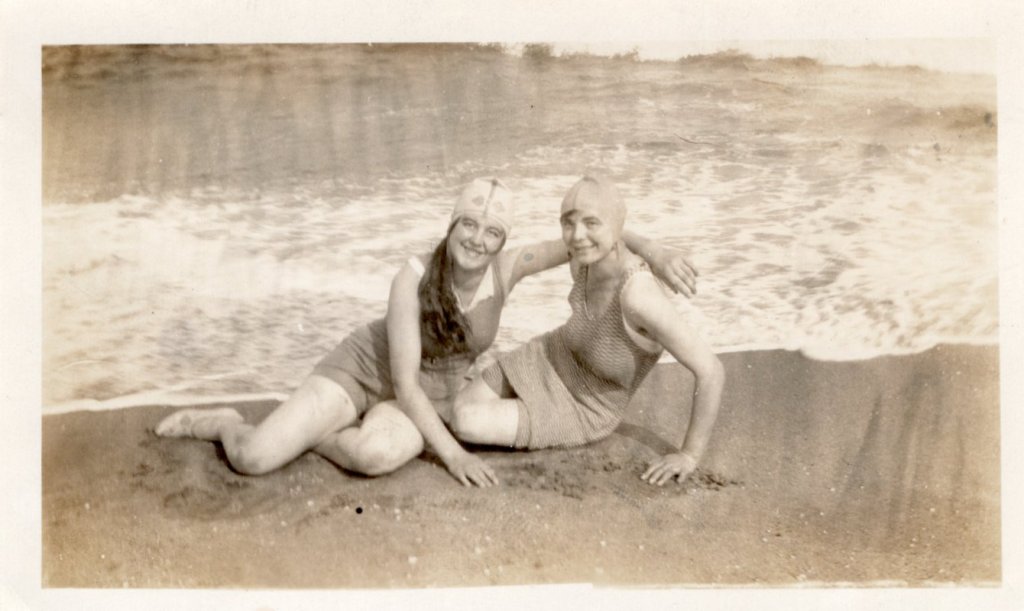

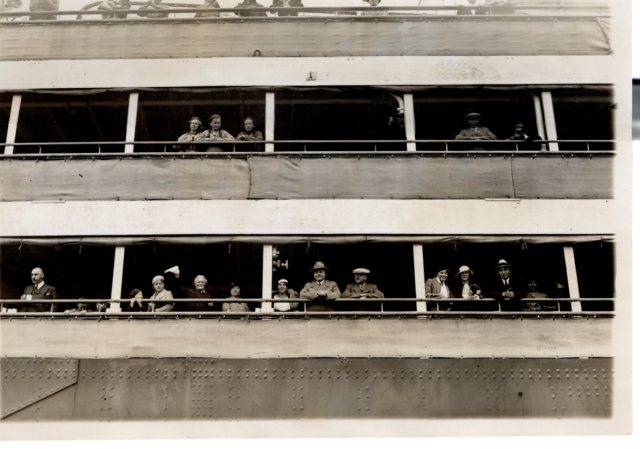

Why would a 16-year-old aunt (who claimed to have been a stuntwoman for silent films shot in Northern Germany) suddenly opt to have an American aunt adopt her, leaving her family behind forever…and what family would allow a 14 year old child—yes, the ship’s manifest revealed the truth—to travel on a boat overseas alone, never to return.

The same 80-year-old Aunt Erna, prim in her pin curls and pearls, would later regal anyone willing to listen with tales of Enrico Caruso serenading her at her restaurant after his Carnegie Hall performances. How she would implore him to sing, and how…just for her…he would relent with one more song after a long night’s show. As a child, I would beg her to tell the story over and over again. Except I now know Caruso died in 1921…and she married my Uncle Henry, the restaurateur, in 1929…and their restaurant only opened in the 1940s…

During countless family gatherings, the same aunt’s secret stash of National Enquirer tabloid newspapers held 10-year-old me enthralled in another room while the adults debated whether a drop of water could ruin a roast or not; my Uncle Henry would hold court in the kitchen, flipping through his now lost restaurant recipe book while entertaining his audience with stories about ice sculptures dripping inconveniently before the advent of air conditioning. Their banter would waft in to me astride scents of deliciousness—how the foodie adult now wishes I would have focused more on them and less on Elvis’ alien love child.

Once everyone is gone, who can confirm whether Estee Lauder really did try to recruit my aunts to help her sell the cream made in her garage? Why did another milliner aunt leave a string of broken-hearted boyfriends behind in Germany only to eventually design hats for divas and dignitaries? Who do you ask about the babies lost, the lives snuffed by pandemics and wartime, the life-changing decisions to leave everything and everyone behind.

I miss my large and vibrant family in all of their glorious colorfulness. I crave the opportunity to talk to them again, to ask about their experiences in their own voices…rather than create a fiction to fill in the gaps. The hardest thing of all is the responsibility of being the last woman standing.