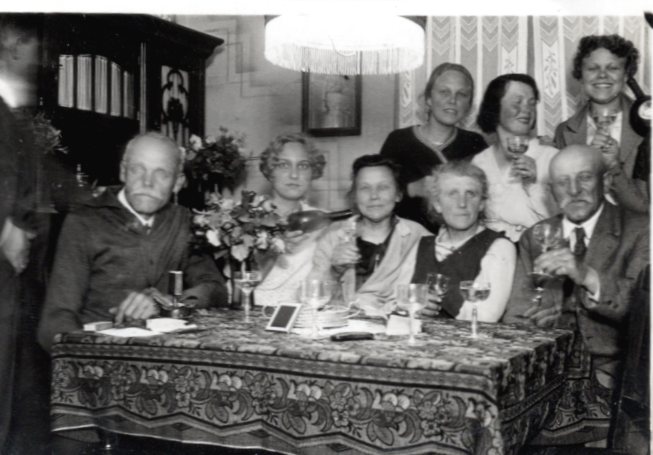

Family Portrait, 1905

Karl, Rose, Great-Grandmother, Great-Grandfather, Betty and Agnes (l to r)

My urge to pursue a career in medicine comes from my maternal grandfather, a family doctor. My specific interest in neurological diseases could also be considered hereditary. Over the years, I watched how cancer and neurological diseases—namely Parkinson’s Disease and dementia—wove their way insidiously through the gene pool of the eleven siblings in my maternal grandmother’s family. My grandmother was the youngest. When she passed in 2012, she had nearly reached the age of 95. She prided herself in staying active, traveling, and keeping a youthful outlook. Despite always acting much younger than her age, in the end her genes betrayed her: her final years were overshadowed with battling the ravages of breast cancer and dementia at the same time.

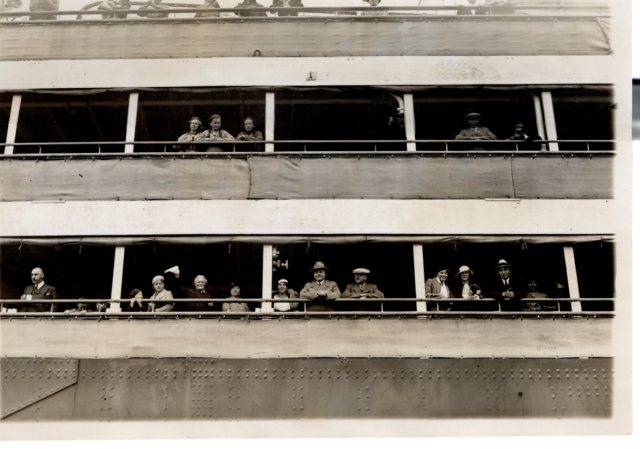

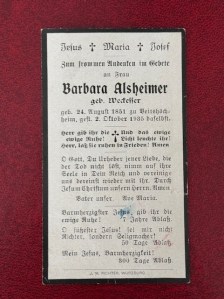

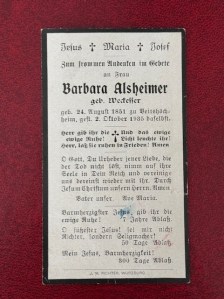

Her parents, my maternal great-grandparents, married in Bavaria, Germany in 1899. Their first child, Agnes, was born in 1900. My grandmother, the youngest, entered the world in 1917, near the end of World War I. Over the span of nearly two decades between the oldest and youngest, the family grew with the births of eleven children.

Four of these eleven great-aunts and great-uncles I never had a chance to meet. Christl, the ninth child, died as a baby. Rose, the fourth, died of cancer shortly after I was born.

And then there were Karl and Betty, the second and third children, respectively. Both were lost, tragically, within a year of each other. Their deaths precipitated a deep family feud that was never forgiven…

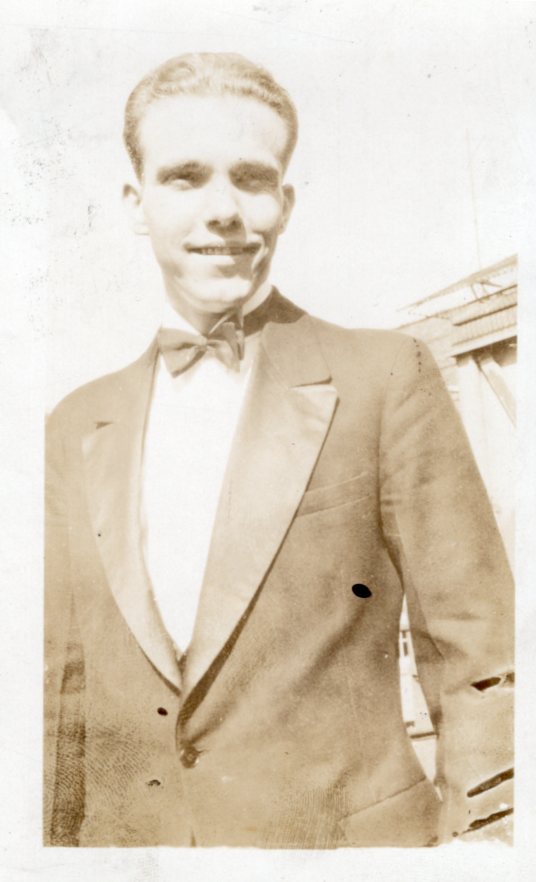

Because they died so young, their stories came in scattered fragments and without much elaboration. One fact was consistent, though: Karl and Betty were my great-grandfather’s greatest pride and joy. Not that my great-grandfather didn’t cherish all of his children; however, these two had particular gifts. While the siblings each came to demonstrate unique skills and creativity in areas such as design, culinary arts, dressmaking, and millinery, Karl’s special gift was music…and it blossomed early. His virtuosity with the violin earned him enrollment at a prestigious music conservatory, and his father could not have been prouder of the honor bestowed upon the young protégé.

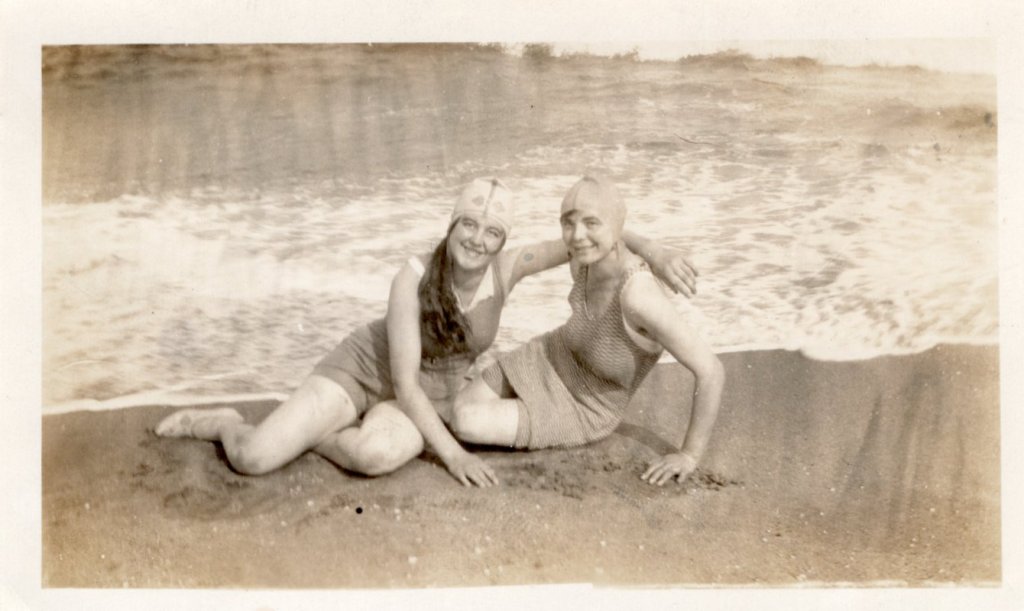

Betty’s gift was her ethereal beauty. It is said that Kaiser Wilhelm II once came to visit the village were the family lived and where my grandfather was a respected town elder. As the Kaiser was greeted by the villagers, a child said to be as beautiful as an angel caught his eye in the crowd. He inquired about the child, calling her forward. Betty was presented to the Kaiser. He complimented her beauty, expressing his hope that when she was older he might meet her again at his court, as the court would be much enhanced by her loveliness. The family was greatly honored by this royal praise for the young girl.

First Communion Portrait of Betty (left) and unidentified girl. About 1910.

With any large and close-knit family, there inevitably comes a moment when a family member arrives seeking help and possibly refuge. Maybe it had to do with the “Great War” — a husband away or a spouse lost at the Front. Or perhaps it was something else. That part of the story remains a mystery. What is known is that the growing household of two adults and nine, possibly ten children, ranging from teenagers to tiny toddlers, took in one more adult. Whether she moved in as a much needed set of additional hands or simply a family member in need, she was welcomed into an overflowing household, taking up residence in the top room of the three-story home.

While the visitor may have been keeping her own company in her room under the rafters, the impact of her arrival was soon to be felt like an earthquake. How the sickness first presented itself, when the family realized what was upon them was never discussed. The outcome remained the same: just a few months after the birth of my grandmother and with a suddenness that took the family by surprise, Betty fell ill…and failed quickly. At first, it was probably a slight slow-rising fever with general malaise, headache and cough; it may have even gone unnoticed given all of the activity in the house. But, by the second week, the fever would have raged out of control, with the onset of delirium and intestinal problems. Most likely, the third week of fever is when she succumbed, the unfortunate victim of an illness for which the War raging around them had just produced a vaccine not yet publicly available. On August 5, 1917, Betty died of typhoid fever. She was not yet fourteen.

One can only imagine the shock this death inflicted on the family. A tragic loss at the height of the Great War; certainly the times were already stretching the family’s reserves, resources, and resolve. As they moved forward from the loss, the time for grieving was likely consumed by the unrelenting needs of an infant and rambunctious toddlers. It was barely a year before it happened again. Stealthily, quickly, and without warning, Karl fell ill like his sister before him…and, in an instant, was gone. His life and musical promise were lost on May 25, 1918, just a few weeks shy of his seventeenth birthday.

Typhoid does not just appear: it usually spreads from person to person, with hygiene and sanitation the best way to prevent it. With two children impacted, the signs now pointed to a close source for the virus. Eventually the quest for answers led to the truth: the visitor living under their roof was a typhoid carrier—she had been harboring the virus in her own body without showing any signs of illness or becoming sick herself.

Upon learning the source of the deadly virus, my devastated great-grandfather flew into a rage. He threw his guest out of the house, and cursed her and her family for bringing this illness into his home. His rage solidified a permanent rift in the family-tree, preventing anyone from that branch of the family from being welcomed under his roof during the remainder of his lifetime.

I have heard it said that my great-grandmother was never the same afterwards. She sought refuge in the quiet of the barn with the milking goats, keeping her own peace, possibly seeking the solitude she needed to cope. I find myself looking at the family portraits taken before and after the loss, noticing that my great-grandfather, an arrow-straight-standing gentleman, no longer stands quite as tall. My great-grandmother’s face, particularly stoic in most portraits, becomes especially drawn-looking. They both lived through battles fought afar and on their own homefront; they may have survived, but a battle-weariness endured.

Summer 2009: I am sitting in my grandmother’s living room in Germany. I have just arrived bearing cake from the bakery and am awaiting her teapot’s whistle announcing water has boiled. I am visiting for “Kaffee und Kuchen” – afternoon coffee and cake – having ducked out of afternoon activities for a medical conference I am attending here, in my family’s hometown. Ironically, the top Germany research experts for the neurological disease I am involved with are based here, in this town…and they are hosting this conference for all of the other specialists from around the World. I am enjoying showing my professional colleagues the town I know as intimately as any tour guide, introducing them to the region’s wine and beer, and proudly showing off the many artistic and historical treasures found at every corner.

Best of all, I can slip away at least once a day and visit with my grandmother.

It has been two years since I have seen her. While physically she can still out-run me up and down the six flights of stairs in her elevator-less apartment building, mentally I am seeing evidence of dementia and several earlier strokes taking hold. Her past memories are sharp and perfectly coherent; however, her ability to retain current information is slipping away from her, and she is repeating things. But she is in good spirits and receiving the care she needs within her own home, so I happily relish the time I can share with her.

I prepare and pour the tea, and she inquires about my day. “How many people are at this conference?”

“About 400.”

She takes the plate with the slice of cake I offer her. “What?! So many? So, why are you here and not there?”

“Because I wanted to be with you.”

“And what is everyone else doing?” She is studying the piece of cake in front of her, not yet tasting it.

“Actually, this afternoon there are tours. One group is going to Sommerhausen, but I’ve already been there.”

“You’ve already been there, you don’t need to go,” she parrots back to me, a bit distracted.

“And the other group is going to the Alzheimer House.”

Her head snaps up from her plate, suddenly she’s fully engaged: “Why would they want to do that?” she challenges.

“Well, I guess since they are a bunch of neurologists, someone thought it would be interesting for them to see Dr. Alzheimer’s house because of Alzheimer’s disease.”

My grandmother becomes agitated. “Why would they want to go to your Aunt Alzheimer’s house? Your grandfather hated that woman.” I’m not sure what to think of her comment; but, before I can react, she has started to make a mental loop through the conversation again, repeating: “Why are you not at the conference this afternoon?”

I offer once more: “Because the neurologists are taking a tour of the Alzheimer House.”

Her reaction is just as abrupt as before; she freezes, and demands again: “Why would they do that? Your grandfather hated that woman.”

But the mental loop her dementia has her caught in does not let her elaborate on her sudden outburst, and I am left with a curious revelation: are we related to Dr. Alzheimer and the Alzheimers?

I query my mother the next morning during a quick call back to the U.S.: “Are we related to the Alzheimers?”

“Your grandfather hated those people,” my mother responding with the same vehemence as my grandmother, taking me completely by surprise.

“So we are related to the Alzheimers?” I ask again, incredulous.

“Of course,” my mother retorts. “Your Aunt Alzheimer was the one who carried typhoid into the house. Your grandfather never forgave her and the Alzheimer family for losing his children.”

Ironically, I have discovered that the name associated with the loss of memory has—for my family—come to represent the memory of loss.

48.790447

11.497889